A look back at the 1947 Tairāwhiti Gisborne tsunamis

26 March is the 77th anniversary of the first of two severe earthquakes that occurred off the coast of Tairāwhiti Gisborne in 1947. This earthquake generated one of the largest tsunamis in New Zealand's historical records. It was observed along 115km of coastline and caused damage to beachside cottages and buildings, bridges, fences, and roads.

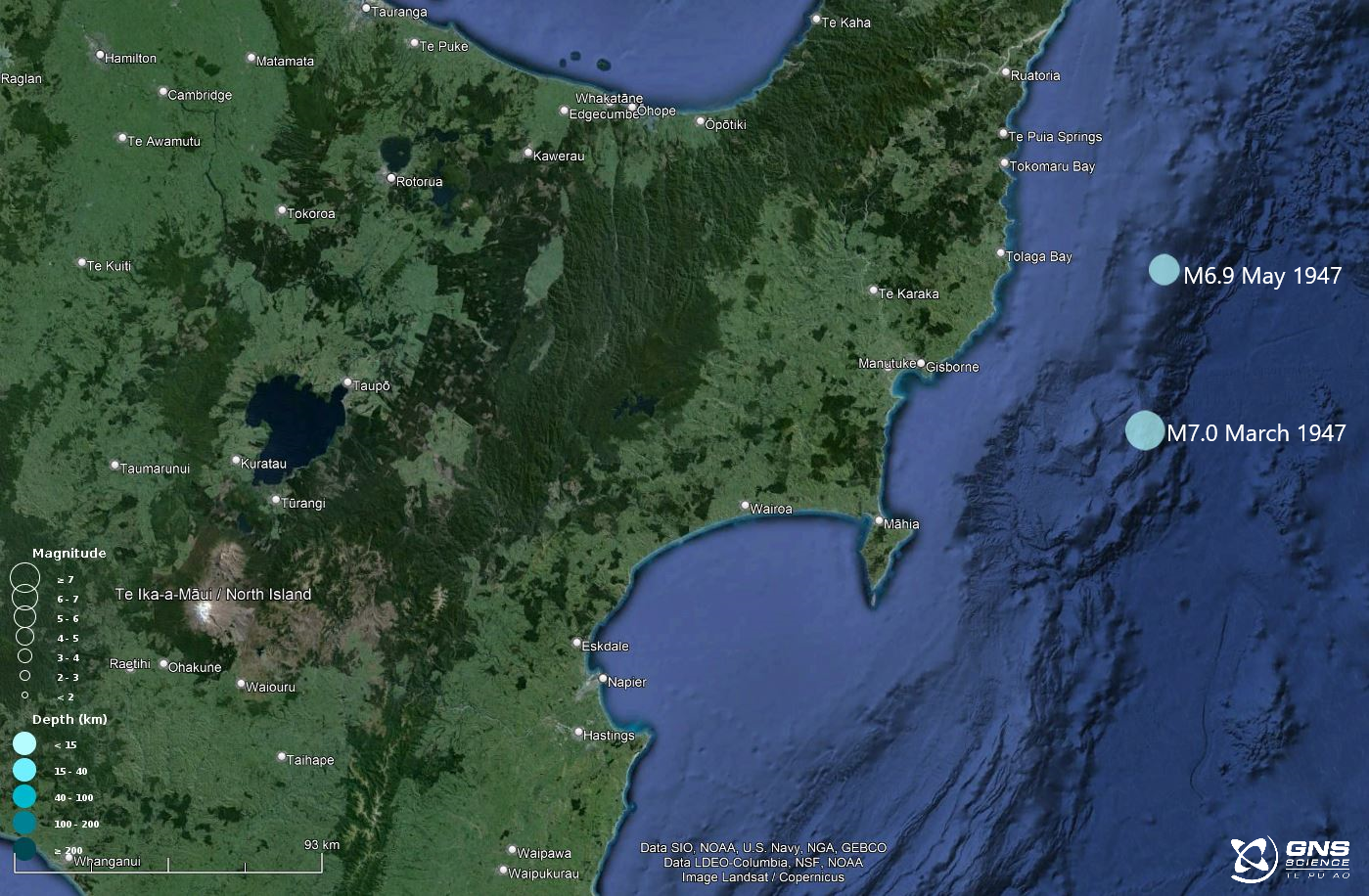

The first earthquake, on 26 March 1947, was a magnitude 7.0 and occurred 70km south-east of Gisborne. Although the ensuing tsunami was large, residents at the time did not report extreme shaking from the earthquake. Scientists think the lack of strongly felt shaking was likely due to a slow rupture.

Slow rupture speed is observed globally for some earthquakes that cause tsunami. As the earthquake occurs it ruptures its fault more slowly than usual (although still much faster than Slow Slip Earthquakes ). The tsunami that these earthquakes produce could be much larger than we would expect from their magnitudes. These types of earthquakes are often called “tsunami earthquakes” and the 26 March event is one of them.

That is one of the reasons for the importance of the ‘or’ in the advice of ‘Long OR Strong get gone’ safety messaging. An earthquake that lasts more than a minute OR makes it hard to stand up is a natural tsunami warning. Find out more on what faults are and how they cause earthquakes in our story here.

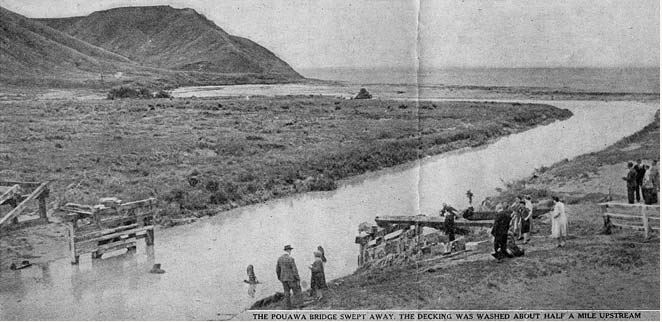

At Pouawa and the south side of Turihaua Point, the tsunami was most evident with large breaking waves said to be 10-13m high observed offshore. At the northern end of Pouawa Beach, where SH35 crosses the Pouawa River, seaweed was found 12m above sea-level in telegraph wires well inland from the beach. The decking and superstructure of a 16m span wooden bridge across the Pouawa River was swept about 800m inland.

At the southern end of the beach, the Hall household was hit by the tsunami and the building swept from its foundation. Three people inside the house were trapped in the kitchen which filled to head height with water. The kitchen was the only section of house not demolished. It was moved 3m and twisted during the first wave, and then during the second wave the rest of the house was smashed and swept out to sea. Two people, who had escaped to the road above the house before the first wave hit, were then washed up onto the road during the second wave.

Four people at the Tatapōuri Hotel, 13 kilometres by road north of Gisborne, saw the tsunami coming and rushed up a hill. Two waves swept through the ground floor of the hotel up to windowsill height, and retreating water then washed small buildings out to sea.

The second earthquake

Just a few weeks later, on 17 May 1947, another offshore earthquake generated a tsunami that hit the coast between Gisborne and Tolaga Bay. This quake, a magnitude 6.9, occurred about 30 km further north, and the greatest damage was at Waihau Beach, where logs piled ready to repair the bridge damaged in the tsunami, two months previously, were washed away.

The tsunami from this second earthquake was not well observed, as it occurred on a stormy winter night about half an hour after the earthquake (about 1.5 hours before low tide). Nevertheless, its effects were noticeable the next day from Wainui Beach, near Gisborne, to at least Tolaga Bay, and possibly as far as Tokomaru Bay, spanning 50-80km of coastline.

Evidence showed that the tsunami travelled further inland and to a higher level than in the March tsunami. Water swept 50m inland at Tolaga Bay and the water height was estimated to be 1.8-2.4m higher than in the 26 March event (likely due to the May earthquake being closer to Tolaga Bay). Taking the tide level into account, this suggests the waves may have reached 4-5m above sea level at Tolaga Bay.

What caused these earthquakes?

These two historic events occurred along the Hikurangi subduction zone, New Zealand’s largest plate-boundary fault. The Hikurangi Subduction Zone and the Tairāwhiti region experience a large range of earthquake sizes and behaviour. In more recent times strong shaking has been generated by the 2007 M6.7 Gisborne earthquake, which did not have a tsunami, and the 2016 M7.1 Te Araroa earthquake, which generated a small tsunami <1m in some places.

While only a handful of the around ~700 earthquakes over magnitude 4, in the region in the last two decades, have caused damage through shaking or tsunami. Ben Green, Tairāwhiti Civil Defence Emergency Group Managers message to the community is “understand the hazard, don’t fear it however be aware of it and have a plan that will focus on you and your whanau getting to safety.”

Live in the Tairāwhiti Gisborne region?

View: Tsunami inundation and evacuation maps for the Gisborne / Tairāwhiti region

Learn: Gisborne / Tairāwhiti region earthquake and tsunami advice

You can learn more about this fault in our series on the Hikurangi Subduction Zone, starting next week. Including where and why it is a focus area for earthquake and subduction research.

Know what to do in a tsunami?

For a local-source tsunami which can arrive in minutes, there is not enough time for an official warning, it is important to recognise the natural warning signs and act quickly. Remember, LONG or STRONG, GET GONE.

If there is earthquake shaking, drop, cover and hold. Protect yourself from the earthquake first, then act as soon as the shaking stops.

If you are near the coast and experience any of the following:

- Feel a strong earthquake that makes it hard to stand up, or a weak rolling earthquake that lasts a minute or more.

- See a sudden rise or fall in water level.

- Hear loud and unusual noises from the water.

Move immediately to the nearest high ground or as far inland as you can, out of tsunami evacuation zones. Do not wait for official warnings.

Once you have evacuated, follow official advice from your local Civil Defence Emergency Management Group about when it is safe to return to tsunami evacuation zones. Do not return until an official all-clear message is given by Civil Defence Emergency Management.

Want to get prepared?

NEMA (National Emergency Management Agency) has a great website with information on what to do before, during and after a tsunami. You can also search your address to find out if it is in a tsunami evacuation zone.

Prepare your home. Protect your whānau.

There’s a lot we can do to make our homes safer and stronger for earthquakes. Toka Tū Ake EQC’s website has key steps to get you started.

Media Contact: 021 574541 or media@gns.cri.nz