Tsunami in Lakes

Updated: Thu Jan 23 2025 10:10 AM

The threat of tsunamis does not just apply to our coasts – lakes can also be vulnerable to tsunamis. Today we investigate what can cause lake tsunamis, where they have occurred in Aotearoa New Zealand, and how we can be prepared for them.

What causes lake tsunamis?

Lake tsunamis can be caused by earthquakes, landslide and rock falls, volcanic eruptions, dam ruptures and glacier collapses.

Have we had lake tsunamis in New Zealand?

New Zealand is home to over 3,800 lakes and we know at least 74 lake tsunamis have occurred in New Zealand from 1846 to 2022, according to a recent report by Department of Conservation, the most recent following a strong earthquake at Taupō in 2022.

The 2022 Lake Taupō tsunami

The M5.7 Taupō earthquake on Nov 30, 2022, caused a small tsunami in Lake Taupō. The tsunami was recorded on lake-level gauges and responsible for pumice and wooden-stick deposits found in many shoreline locations around the lake, with the furthest inshore inundation of around 42m from the lake edge measured at Wharewaka Point.

Further investigations (including an aerial drone survey and a lake dive) highlighted the disappearance of part of the carpark at Wharewaka and the existence of a large and recent underwater slump. Numerical modelling of the tsunami waves shows that there may have been two distinct tsunamis occurring at nearly the same time: the first one triggered by the earthquake rupture in the vicinity of Horomatangi Reef, which was able to reach a large part of the lake; and a second one triggered by the underwater landslide at Wharewaka Point, that explains the large inundation distance nearby but not recorded outside of Tapuaeharuru Bay. The reason for this is that waves triggered by a landslide like the one at Wharewaka disperse quickly in time and space.

In the aftermath of the event, we have installed a new lake-level gauge at Horomatangi Reef in central Lake Taupō to provide real-time monitoring of potential unexpected waves and other lake-level variations which signal unrest of the volcano, underwater landslides, or other wave-generating processes. This data is available on our website here (Sensor code: HRMT).

2011 Tasman Lake

The 22 February 2011 Christchurch earthquake triggered a huge section of ice (1.2km long, 300m high and 75m wide!) to fall from the end of the Tasman Glacier, New Zealand’s largest glacier, into Tasman Lake causing a tsunami. Visitors to the glacier on boats at the time of the M6.2 earthquake, endured 30 minutes of waves, up to 3.5 metres high.

1992 Lake Tekapo

In May and September rock avalanches fell from Mt Fletcher at the head of the Godley River that feeds Lake Tekapo and travelled down the Maud Glacier creating tsunamis in the lake at the end of the glacier. Icebergs were left stranded 20 metres above the normal lake level by the first tsunami, and Lake Tekapo was raised around 90mm.

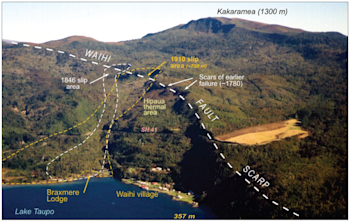

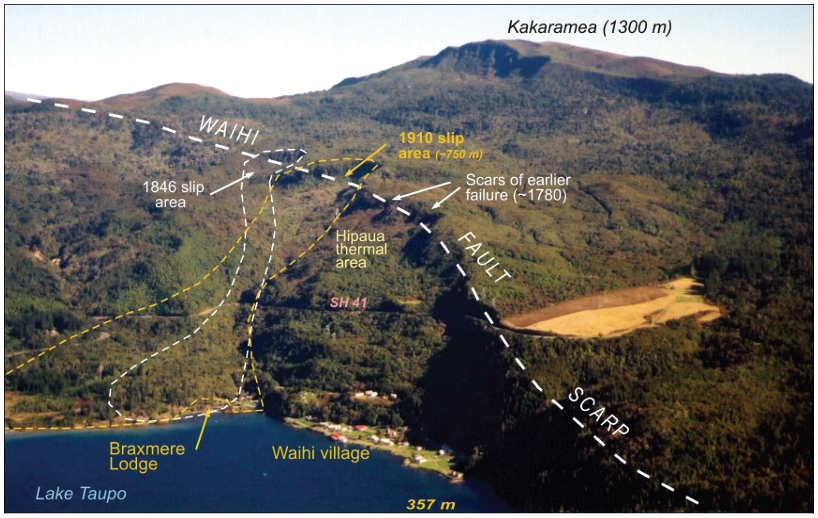

1846/1910 Wahi Landslides

Waihi, at the southern end of Lake Taupō, has had many landslides throughout history, the most devastating was in 1846 where a landslide overwhelmed the Māori village of Te Rapa, killing the chief and 63 members of his tribe. This landslide is thought to have caused a tsunami on the lake with newspaper reports describing people 'seeing the splash of the Taniwha’s tail as he crossed the lake’. In traditional Māori history, large waves, storm surges, and tsunamis were commonly explained as the work of a taniwha. In 2009, GNS Scientists used landslide-generated wave modelling for this site that produced similar wave patterns to those described in the Māori account.

In March 1910 another landside descended into Waihi Bay. News articles reported that the landslide killed one person before it reached the lake and caused a wave of up to 3m high. This wave travelled to the opposite shore of the lake sweeping children off their feet where they were rescued with great difficulty, and all boats and canoes on the lake were reported to have been washed away.

On November 5 2024, World Tsunami Awareness Day, it was 20 years since the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami that shocked the world - are we better prepared 20 years on?

How can we be prepared?

Although most people know that New Zealand’s coastline is at risk of tsunamis, it’s important to remember that they can also happen at lakes. Knowing the warning signs and the right action to take can help save lives - don’t wait for an official tsunami warning.

When you're near a lake front, remember Long or Strong, Get Gone. If you feel a strong earthquake that makes it hard to stand up, or a weak rolling earthquake that lasts a minute or more you should move to higher ground as soon as it is safe to do so.

Not all tsunamis will come with warning signs like earthquake shaking. If you hear loud and unusual noises from the water, or see unusual waves suddenly occurring without an obvious cause (such as the wind or a boat), or see unusual eddies or sudden rises or falls in water level, move away from the lake. If you are visiting one of our amazing glaciers, keep in mind that a glacier collapse could trigger a lake tsunami.

Know what to do?

All New Zealanders should be prepared in case of a natural disaster. Follow the National Emergency Management Agency’s guidance on how to make sure that you and your whānau will get through an emergency.

Prepare your home. Protect your whānau.

There’s a lot we can do to make our homes safer and stronger for natural hazards. Natural Hazards Commission Toka Tū Ake's website has key steps to get you started.