Today is World Tsunami Awareness Day

In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly designated 5 November as World Tsunami Awareness Day to promote a global culture of tsunami awareness. To mark this day, we will take a glance at Aotearoa’s history of tsunami and what causes them.

When it comes to tsunami, “Long or Strong, Get Gone!” is an important thing all New Zealanders must know and act on. Every minute and every metre counts. After an earthquake that is longer than a minute or is hard to stand up in, a tsunami may be only minutes away for some places. So, don’t wait for anything, evacuate coastal areas immediately and stay away from the coast until given the official all-clear.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, we have a long history of tsunami. Mātauranga Māori of tsunami that occurred pre-European arrival (some of which were devastating) provides vital knowledge for helping us understand and prepare for future events. Our coastlines also contain evidence of these past tsunami, recorded in the geology as layers of shell, sand and tiny marine creatures that were washed up by the event. Since the 1840s, letters and newspaper articles have recorded the tsunami – there have been at least 68, with six more than 5 metres high! You can learn more about these events from our New Zealand Tsunami Database.

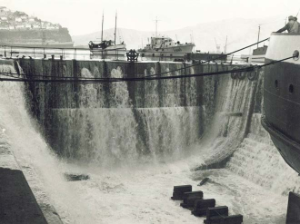

Tsunami can be a few centimetres to tens of metres. In a similar way to earthquakes, small tsunami visit us more frequently than large ones. One of the biggest in recent history was in 2016 after the M7.8 Kaikōura earthquake. This caused one of the biggest local source tsunami in Aotearoa New Zealand since 1947 (local sources are those that are less than an hour’s travel time away). The Kaikōura earthquake ruptured many faults and extended to offshore faults which generated the tsunami.

The earthquake also uplifted the coastline, making things even more complex. You may have read that the tsunami was 7 metres high near Kaikōura. This sounds huge, but it’s not quite the 7 metre wall of water at the coast that it sounds like. This figure referred to the 6.9 metre ‘run up’ measured in Goose Bay, just south of Kaikōura. The tsunami wave height in the sea was probably around 3-4 metres above the normal sea level at the time when it reached Goose Bay, but the beach there is very steep and the wave pushed up against it, leaving debris up to 6.9 metres above sea level. The tsunami also pushed at least 150 metres up the Ote Makura Stream in Goose Bay, and over 200 metres up Te Moto Moto stream in Oaro.

The tsunami was large enough to damage a house in Little Pigeon Bay in Banks Peninsula, well to the south of the earthquake. It was very lucky that nobody was on the shore or staying at Little Pigeon Bay cottage at the time.

What causes tsunami and where do they come from?

Tsunami are caused by sudden, large scale displacements of water. Volcanic activity, underwater or coastal landslides, or earthquakes can move large amounts of water very quickly. Sudden changes causes the water to flow away from the disturbance, generating tsunami waves.

In New Zealand, we categorise tsunami into three types:

Local tsunami are generated very close to New Zealand and are less than an hour’s travel time away. These can come from our offshore faults, volcanoes and canyons which might generate submarine landslides. For some places a tsunami may arrive at our coastline within minutes.

Regional tsunami are generated between one and three hours travel time away from coastal impact. An eruption from an underwater volcano in the Havre Trough (sea north of the Bay of Plenty) to the north of New Zealand, has generated regional tsunami.

Distant tsunami are generated from a long way away, such as from across the Pacific in Central or South America. In this case, we will have more than three hours warning time for New Zealand.

Boundaries between two tectonic plates can generate very large magnitude earthquakes and tsunami. Where one plate pushes under another, this is called a subduction zone and these have generated massive tsunami such as the 2011 Tohoku Japan tsunami. Closer to home we have our very own… the Tonga-Kermadec and Hikurangi Subduction Zone off the East Coast of the North Island and the Puysegur Subduction Zone south of the South Island.

Scientists and Civil Defence Emergency Management (CDEM) have been working together to model earthquake and tsunami scenarios for plate boundary earthquakes at the Hikurangi Subduction Zone to inform response planning. Here's a video showing these scenarios.

This is the first of two stories to discuss tsunami in New Zealand, next up we look at how we know a tsunami is coming, and how you can be prepared.

Media enquiries: media@gns.cri.nz or 021 574 541