Why do we collect felt reports?

Have you ever wondered why we collect felt reports following an earthquake? Well wonder no more!

Historic role of felt reports

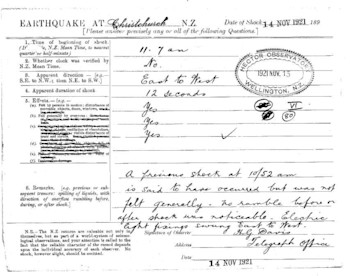

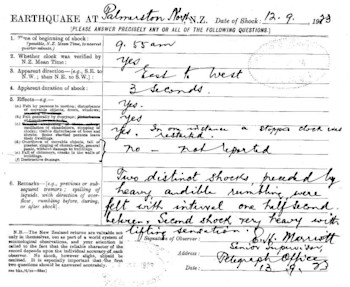

Seismologists began collecting felt reports back in the early 1900s. This was well before GeoNet and the network of instruments across Aotearoa New Zealand existed. To get the information about shaking at different locations, dedicated volunteers filled in paper questionnaires and sent them to the observatory in Wellington. Before the 1930s these felt reports, along with newspaper clippings, were used by scientists to calculate where an earthquake was located (not a speedy process!). As most people in New Zealand lived by the coast at that time, not much was known about the earthquakes further inland.

Modern role of felt reports

Fast-forward to today, with our modern network of sensors across Aotearoa New Zealand, we have instrumentally recorded earthquake information on our website and app within minutes. However, you’ll still see a ‘Felt It?’ button when you look at GeoNet to find an earthquake. So why do we still collect felt reports?

Our network of sensors allows us to accurately determine both the location and size/strength of an earthquake. The sensors are extremely sensitive and often record earthquake shaking that wouldn’t be strong enough to be felt by people. To understand the effects from a specific earthquake we need more than just the earthquake size and location. The level of shaking experienced at a location is dependent on the distance from the earthquake source, the kind of building you are in, and the ground material underlying and surrounding that place.

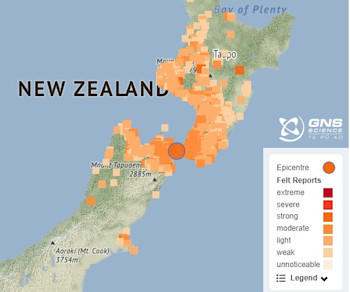

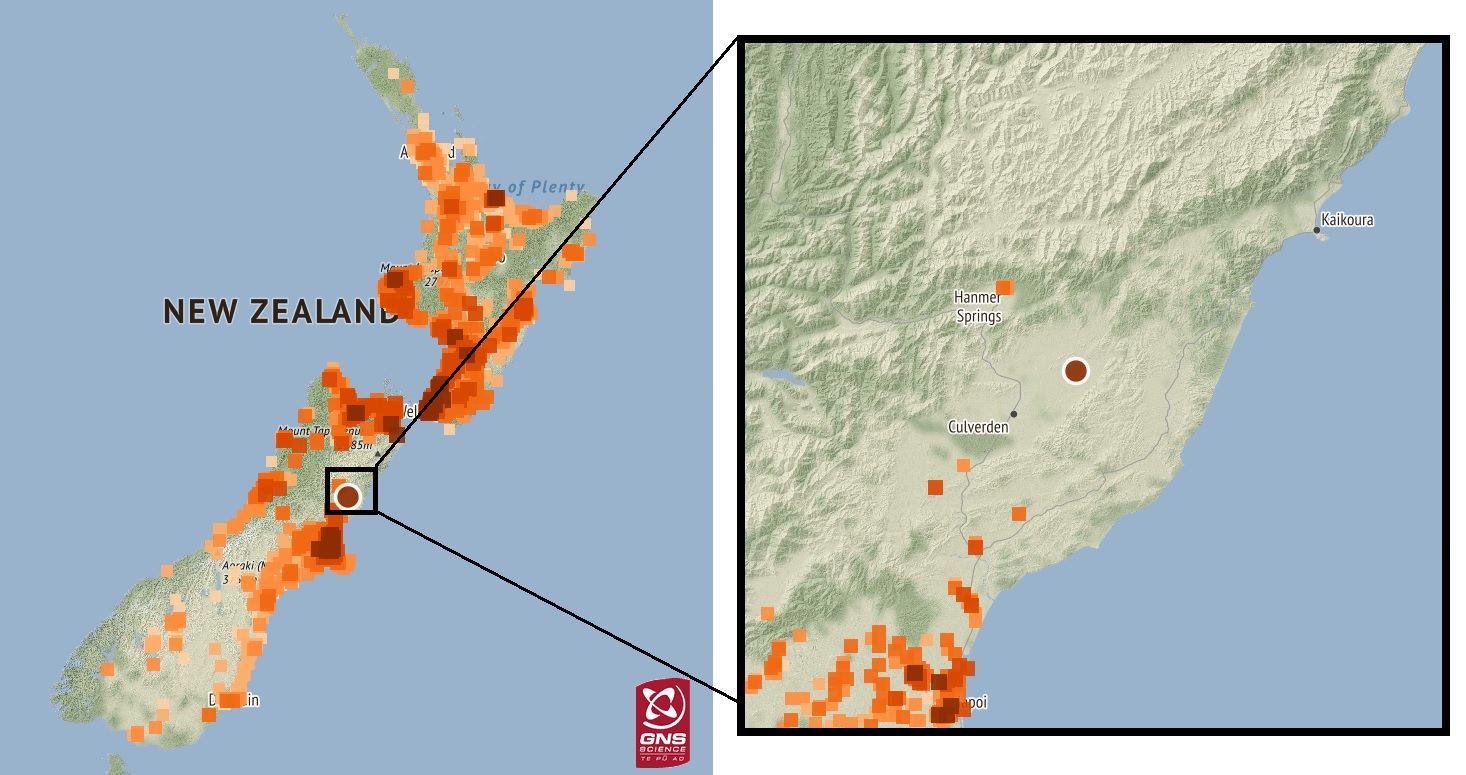

Felt Reports help us go beyond the earthquake location and see how widely and how strongly an earthquake was felt, for example this M5.7 Cook Strait earthquake in October (which received 37,298 reports!).

Watch: Why do we get earthquakes in New Zealand?

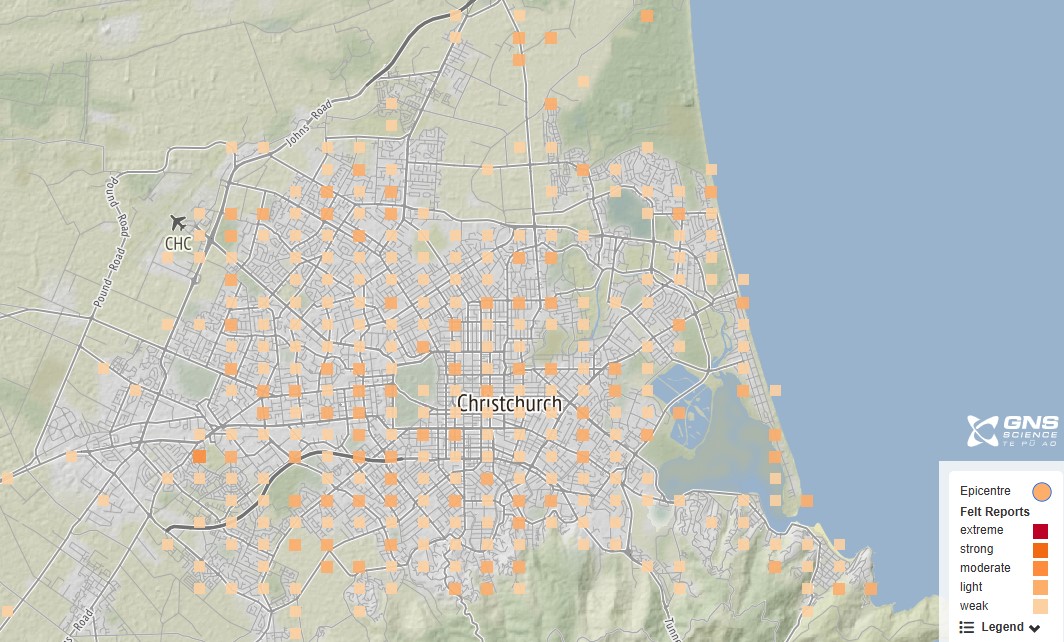

Each earthquake that we publish on our website and app has an associated felt report map. They display the median (middle) shaking intensity experienced in a particular area, to better reflect how most of the people that completed a felt report felt shaking at their location.

Each of the individual squares on our shaking map contain all felt reports received within approximately a 1km area. We group them in this way to protect your privacy. The square tiles overlap with one another (when we're zoomed out) so the map display shows the tiles with the most felt reports on top and those with fewer reports underneath. This helps mitigate some of the sparser areas where one report might say extreme, but nearby ones are weak/light.

Prior to the introduction of the Shaking Layers maps, Felt Reports were the best way to get a quick assessment of the extent and effects of an earthquake. Although, for small earthquakes Felt Reports still play the same role in quickly assessing shaking extent that they have for the past decades, as Shaking Layers is designed to focus on the impacts of larger earthquakes (M3.5+). For larger earthquakes, felt reports are still an extremely useful tool for emergency services in the first minutes following an earthquake when there isn’t much information immediately available about what impacts the earthquake may have caused.

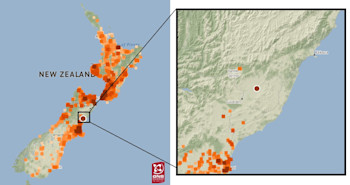

They provide a rapid indication of how widely and strongly an earthquake was felt, which helps emergency responders make decisions about how to support impacted communities if needed. An absence of felt reports where we might normally expect to see them after an earthquake is a useful data point that cannot be provided by calculations of potential shaking. This can be an indication that there may be communications and power outages in the area impacted by the quake – this is what we saw in the felt reports from the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake, where fewer felt reports were registered closest to the earthquake epicentre in Kaikōura compared to other districts nearby.

Felt Detailed - back to the future

While we no longer rely on dedicated volunteers to locate earthquakes, detailed reports of earthquake shaking and experiences during an earthquake are still useful in both immediate earthquake response and long-term research projects. There will always be far more people than earthquake sensors in Aotearoa New Zealand. Just like in the past and submitting rapid ‘Did you feel it? information, people can act as ‘human sensors’ that help us build a detailed picture of the shaking at their location.

The Shaking Layers maps mentioned above are built on a set of equations that use earthquake information generated from the sensor network, a model of land structure and distance to calculate the expected shaking from a particular earthquake. Scientists then use the strong-motion data GeoNet receives from its stations around New Zealand to check and update these shaking calculations. In order to do the same kind of checking in between sensor locations, submitted reports of shaking intensity can be used to check and correct the areas where the most intense shaking occurred. If you’d like to help and submit this kind of information, then look for the ‘Felt Detailed’ button (a longer questionnaire of around 40 questions) next time you are checking out an earthquake on our website. In addition to their potential for near real-time use, ‘Felt Detailed’ reports are also being used for several research projects, including ‘community intensities’ which provide an easy way to understand the distribution of shaking caused by an earthquake in New Zealand. Using these, scientists have created a database of more than 170,000 community intensities for earthquakes from 2004 to the present, using the online felt reports provided by the public.

These are also being used for monitoring tsunami evacuation rates and informing and validating evacuation modelling being undertaken by GNS Science and external researchers.

We would like to take the opportunity to thank all the people in New Zealand who have generously filled in felt reports (both the long and short versions), providing us with an immensely valuable amount of information. Whether you have in the past or not, we invite you to take part and help us gather this earthquake data in the future either through submitting a rapid or detailed felt report. Thank you!

Acknowledgements Shaking Layers is a GNS Science product supported by GeoNet and the Rapid Characterisation of Earthquakes and Tsunami (R-CET) programme.

Earthquakes can occur anywhere in New Zealand at any time. In the event of a large earthquake: Drop, Cover and Hold.

Remember Long or Strong, Get Gone : If you are near the coast, or a lake, and feel a strong earthquake that makes it hard to stand up OR a weak rolling earthquake that lasts a minute or more move immediately to the nearest high ground or as far inland as you can, out of tsunami evacuation zones.

Know what to do?

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) has a great website with information on what to do before, during and after an earthquake.

Prepare your home. Protect your whānau.

There’s a lot we can do to make our homes safer and stronger for natural hazards. Natural Hazards Commission Toka Tū Ake's website has key steps to get you started.