We know long or strong, get gone. But what about tsunamis when the earthquake is far away and we don't feel it?

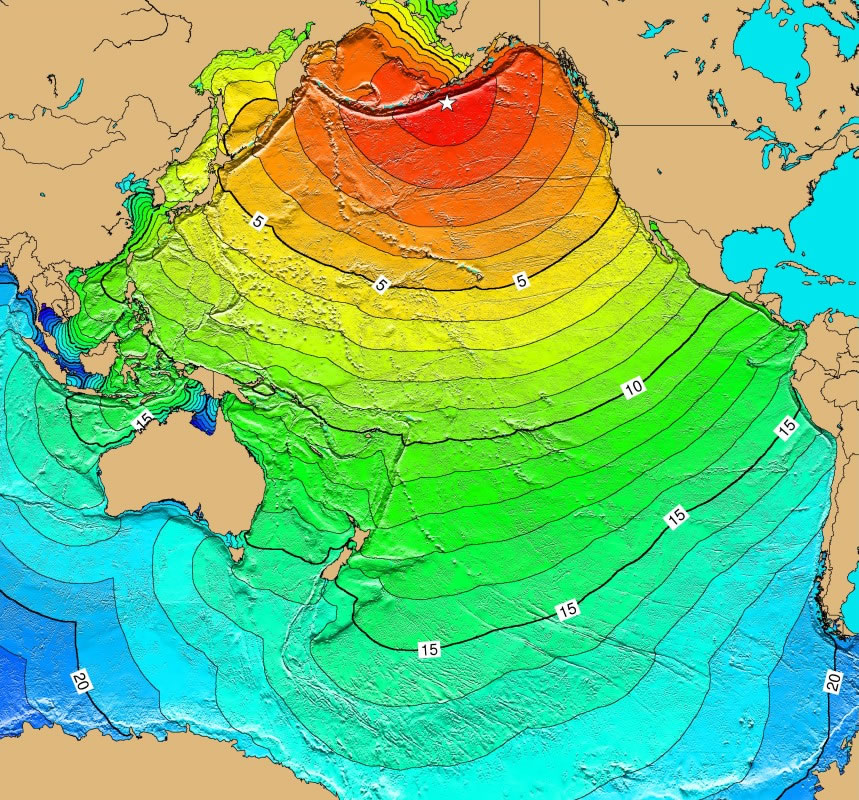

In light of last week’s M7.9 Aleutian Island earthquake in Alaska, we thought it might be worth having a look at how we monitor for tsunamis coming from across the Pacific Ocean.

We know we are meant to go inland or to higher ground straight away if we feel a long or strong earthquake. A strong earthquake, when shaking makes it hard to stand up, or a long earthquake with shaking that lasts more than a minute, could generate a tsunami that arrives within a few minutes to a few hours.

If you are unsure whether you need to leave the coast, or where you need to go, check out your local Civil Defence pages and your local tsunami evacuation zones

But what do we do about tsunamis when the earthquake is far away? How are we even going to know that a tsunami might be on its way? We call these tsunamis ‘distant source tsunamis’ because they are coming from a long way away and the tsunami waves might take between a few hours and a day to arrive in New Zealand.

It may seem weird that a tsunami generated thousands of kilometres away on the other side of the Pacific Ocean could still be big enough to pack a punch when it gets here, but tsunamis created by big undersea earthquakes can travel a long way without losing much energy.

In fact, much of New Zealand’s tsunami damage over the last 180 years has been the result of distant source tsunamis, particularly ones created off the South American coast. The size of the punch in New Zealand depends on where around the Pacific Ocean the earthquake happened, how big it was and whether the sea floor moved mostly up/down or mostly sideways. The more up/down movement of the sea floor, the bigger the tsunami.

In case you missed it, GNS Science scientist Dr Graham Leonard talked to Breakfast host, Jack Tame about the 7.9 Aleutian Earthquake that occurred southeast of Kodiak Island in the Gulf of Alaska last week. You can watch the interview here - Graham has some really clear explanations.

One of the key points that Graham makes about distant source tsunamis is that if any one of those factors about the earthquake had been different (location, size, and the sea floor movement) we could have had a different impact in New Zealand.

GeoNet’s network doesn’t cover the entire big blue space surrounding us but our friends at the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Hawaii monitor earthquakes all around the Pacific Ocean. We use information from their network to assess whether a tsunami may be on its way to New Zealand.

The PTWC will send out a Tsunami Information Bulletin as soon as they detect a significant earthquake anywhere in the Pacific Ocean, whether a tsunami has been generated or not. GeoNet receives these bulletins and if the earthquake could have generated a damaging tsunami, we will spring into action.

GNS Science has made hundreds of computer models of tsunami impacts from possible earthquakes around the Pacific. In the early minutes after a big earthquake, we look at these models to get a rough idea of what the impact here might be, given the initial estimates of the earthquake magnitude.

If any of these computer models or any other information we have suggests that there is a tsunami threat, GeoNet activates the Tsunami Experts Panel (TEP). The TEP is a group of experts from throughout New Zealand who assess earthquake, tide gauge and open ocean pressure sensor (DART buoy) data to see if the earthquake is likely to have generated a tsunami that could affect New Zealand.

Often in the early minutes after a large Pacific Ocean earthquake there isn’t enough information to conclusively say whether or not New Zealand is at risk. But as the TEP keep working and more information becomes available, we can provide more detailed information.

We often won’t have a good handle on whether a tsunami has been generated until about an hour after the earthquake (remember, most distant source tsunamis are generated many hours away from us, so we have a bit more time up our sleeves than for a local source tsunami). The reported magnitude of an earthquake will often change quite a bit in the first 30-60 minutes after it happens as more seismic data is processed, and it also takes a while for scientists to understand how the sea floor moved, if at all.

Depending on where the earthquake happened, it also takes many minutes for any tsunami to reach an open ocean tsunami sensor (DART buoy), but that is our best evidence of whether or not a tsunami has in fact been created. If you’re interested, we wrote about how we assess tsunamis that could be coming our way after the Mexican earthquake and tsunami in September.

We saw this play out last week during the M7.9 Aleutian earthquake where the reported magnitude changed three times in the first hour. After about 20 to 30 minutes we also received more seismic data that suggested the earthquake’s movement was a combination of side-to-side and up/down. While this still has the potential to generate a tsunami, it’s not the worst case, which is entirely up/down movement. Again, Graham has a nice explanation of this in the video above.

Many big earthquakes in the Pacific Ocean won’t cause a noticeable tsunami here. But even in this situation GeoNet continues to monitor the situation just in case Mother Nature throws something unexpected at us and we need to re-evaluate the hazard.

On the odd occasion though, an earthquake will be big enough to move the seafloor and be in the right (or, for us, wrong!) location to send a tsunami big enough to be dangerous our way. Most of these tsunamis will not flood land, so you may not need to evacuate your home, but they may cause strong and unpredictable currents and surges in the water. These can be dangerous to people and boats in the sea, so it is important for boaties and other people in or near the water to know to that something is on the way.

Perhaps a couple times in a lifetime a distant source tsunami will be big enough to flood land in New Zealand, and you may need to evacuate if you are in a low lying area.

GeoNet works really closely with the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Managment after a significant Pacific Ocean earthquake, providing our scientific advice so that they can advise New Zealand what is happening and issue warnings if necessary. They have a useful factsheet that explains how their tsunami warning system works.

The best place to go to for information on whether you are in a tsunami evacuation zone (the area that you may need to get out of in an official tsunami warning, or after a long or strong earthquake), and how you will be told if there is a tsunami coming from across the Pacific Ocean, is your regional CDEM Group or your local city or district council.

Written by Helen Jack and Emily Lambie.

Science Contact: Bill Fry, GNS Science.