The Grand Canyon of Rotorua – a subterranean landslide in volcanic soil along an earthquake fault

The heavy rain in Rotorua District over the weekend created and reactivated several collapse holes. We have a look at how these things form.

The formation of collapse holes, locally known as ‘tomo’, is very common in the soft, easily eroded pumice-based soils of the Rotorua-Taupo area. The holes most commonly form when water seeping into the ground washes away finer particles, creating an underground cavity or tunnel – a path for water to flow in. The eroded soil is carried away into the porous volcanic rock underneath.

Faults make easy pathways for water to flow into the ground, so these cavities will often form along faults, or at the bottom of fault scarps. Eventually a cavity can get so big that the overlying land falls into it, and boom – a collapse hole or tomo. This process can happen quickly, over the course of a few hours.

Before the cavity collapse there might not be any evidence, or only very subtle evidence that this underground erosion is happening. Many are discovered by tractors or fertiliser trucks driving across what appears to be solid ground.

The collapse holes most often appear during heavy rain, when water ponds in low lying areas or old craters, and existing collapse holes can reactivate and get bigger during heavy rain.

Earthquake Flat, where the most recent collapse hole has formed, is a unique area about 15 km southeast of Rotorua. It is the summit crater of a volcano that erupted about 60,000 years ago, flinging 50 cubic kilometres of pumice across the surrounding countryside. This has created a basin of ‘internal drainage’, which means that there no streams flowing out of the crater – all the rain that falls in the crater must slowly drain out through the pumice soils in the basin floor.

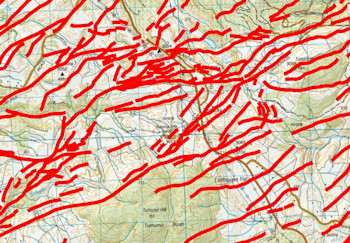

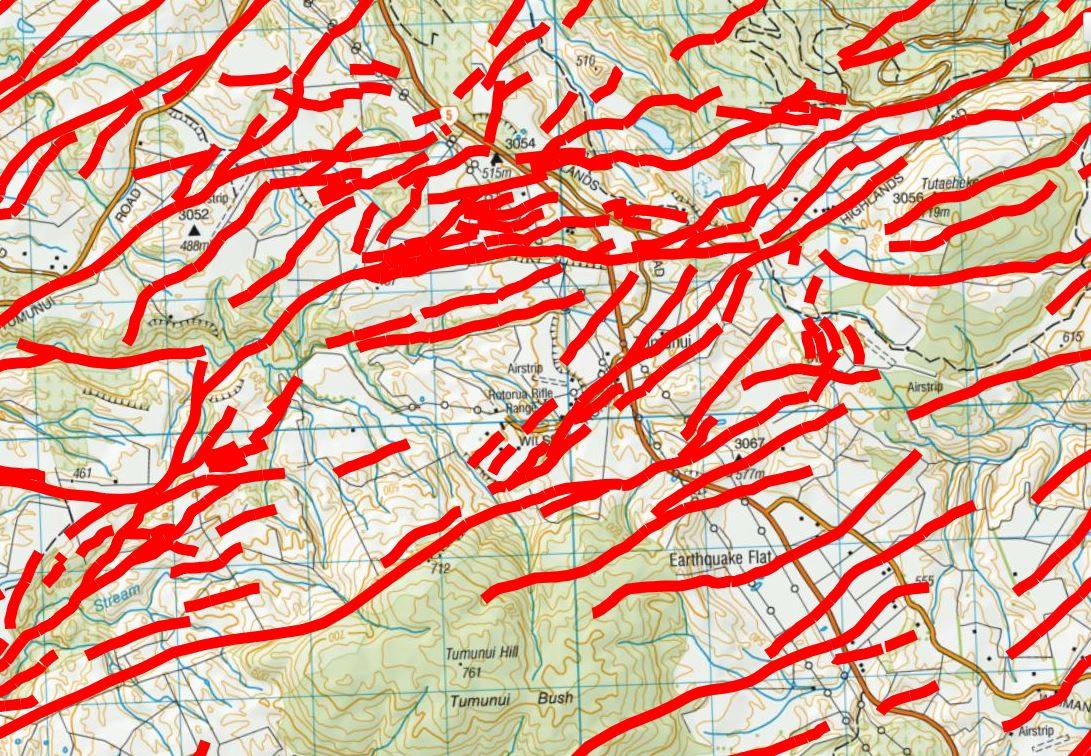

The Earthquake Flat crater is also criss-crossed with faults of the Taupo Fault Belt, and it is these faults that provide a convenient path for water to seep into, eroding away the soil as it goes. Last weekend’s downpour – almost 170mm of rain in 38 hours – created the perfect storm for a collapse hole to form. You can check out some great footage on RadioNZ, TVNZ and Newshub.

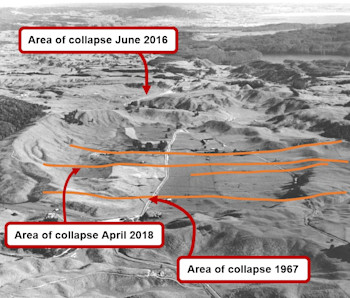

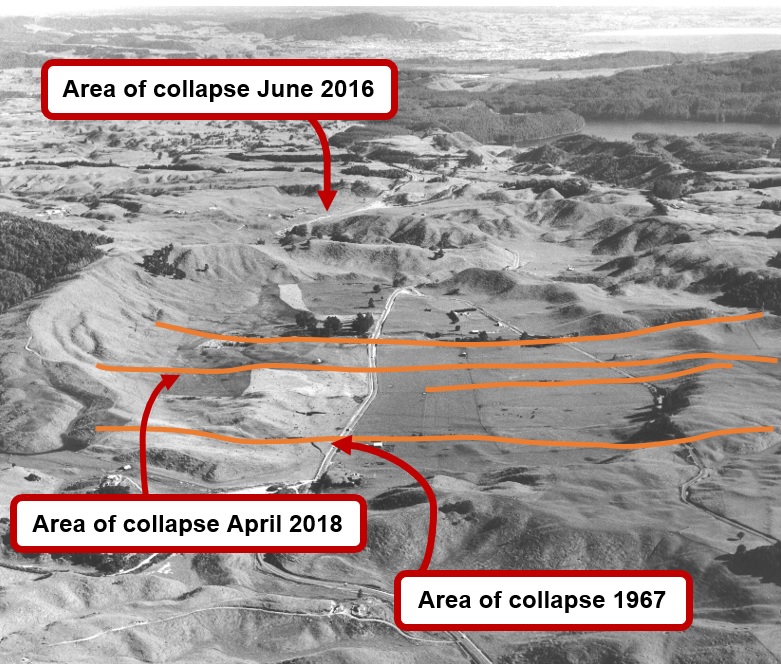

While last weekend’s collapse hole is particularly large, and inconvenient for the farmer who must now work around it, these sorts of features aren’t unusual around Rotorua. In 1967 part of State Highway 5 about 1 km east of this latest tomo collapsed under similar circumstances, again along one of the faults in Earthquake Flat crater. And a smaller collapse hole opened up in June 2016 near Wilson Road in what is known as Rifle Range Crater, another basin of internal drainage just to the north of Earthquake Flat crater. To date only roads, farm trails and pasture have been affected by these features.

The one good thing about collapse holes is that they give our volcanologists a fascinating view back through tens of thousands of years, providing a few more pieces in the puzzle of the Taupo Volcanic Zone’s history. We can see the layers of lake sediments, quietly formed on old lakebeds over long quiet periods, punctuated by layers of ash and pumice from relatively short but violent eruptions.

A few people have asked if these collapse holes have anything to do with earthquakes. They do tend to occur along earthquake faults, but this is because the ash or rocks along faults has been smashed up during movement on the fault over thousands of years, so it is more easily washed away during heavy rainfall. The collapse holes are not related to any recent earthquakes.

The Earthquake Flat tomo is not going anywhere in a hurry, so our volcanologists and landslide scientists will be heading up to check it out over the next few weeks. We are investigating reports of other collapse holes that have opened during the weekend’s rain, including two on another nearby farm, and we're also collating information on landslides that occurred.