2019 - In Review

Tragically, 2019 ended with the Whakaari/White Island eruption of 9 Dec The eruption had devastating impacts for people on the island at the time, our thoughts continue to be with the families and friends of the people who lost their lives and were injured

We live in a beautiful country with a unique landscape, but it’s easy to forget that it was formed through events such as earthquakes, landslides and volcanic activity, that many of us dread occurring. All through 2019, we saw this moving and changing of our landscape, from small earthquakes to the dramatic and tragic events on Whakaari/White Island. Here’s a quick look back at the year, and a reminder that although we may not look forward to them happening, we can prepare and keep ourselves, and our whānau safe during these events.

Earthquakes

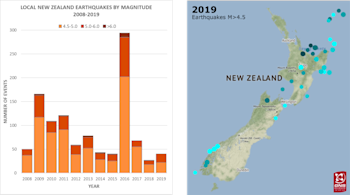

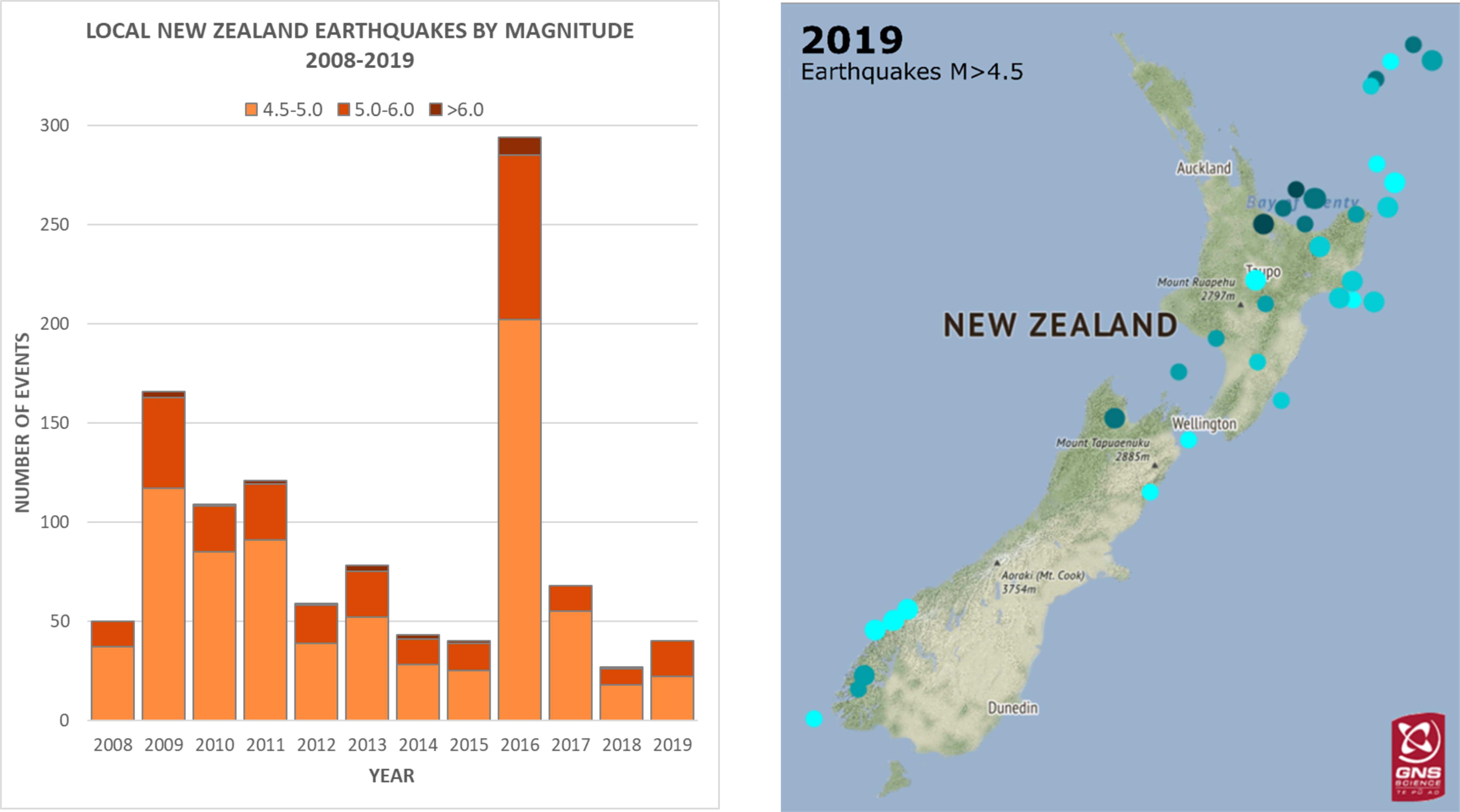

Starting with earthquakes, 2019 was a relatively quiet year, we located 22,169 earthquakes throughout New Zealand. The graph below shows more local earthquakes over magnitude 4.5 located since 2008. Last year we had 137 (the large spike in 2016 is due to the Kaikoura Earthquake and aftershock sequence).

Heading around New Zealand we start at Northland where a swarm of 39 earthquakes occurred at the beginning of 2019. This was a surprise to locals as this area isn’t known for frequent earthquakes. Earthquake swarms are quite common in New Zealand, and while they may sound scary, swarms are simply a group of quakes about the same size, happening in a localised area, usually over a short time period (days to weeks).

Taupo, no stranger to earthquake swarms, had their own in July with over 160 earthquakes in one week. These were located under the lake, and just South of Turangi. Also in Lake Taupo a M5.2 earthquake occurred in September, this was felt by over 4000 people and was followed by a M4.5 aftershock and a sequence of 80 smaller aftershocks.

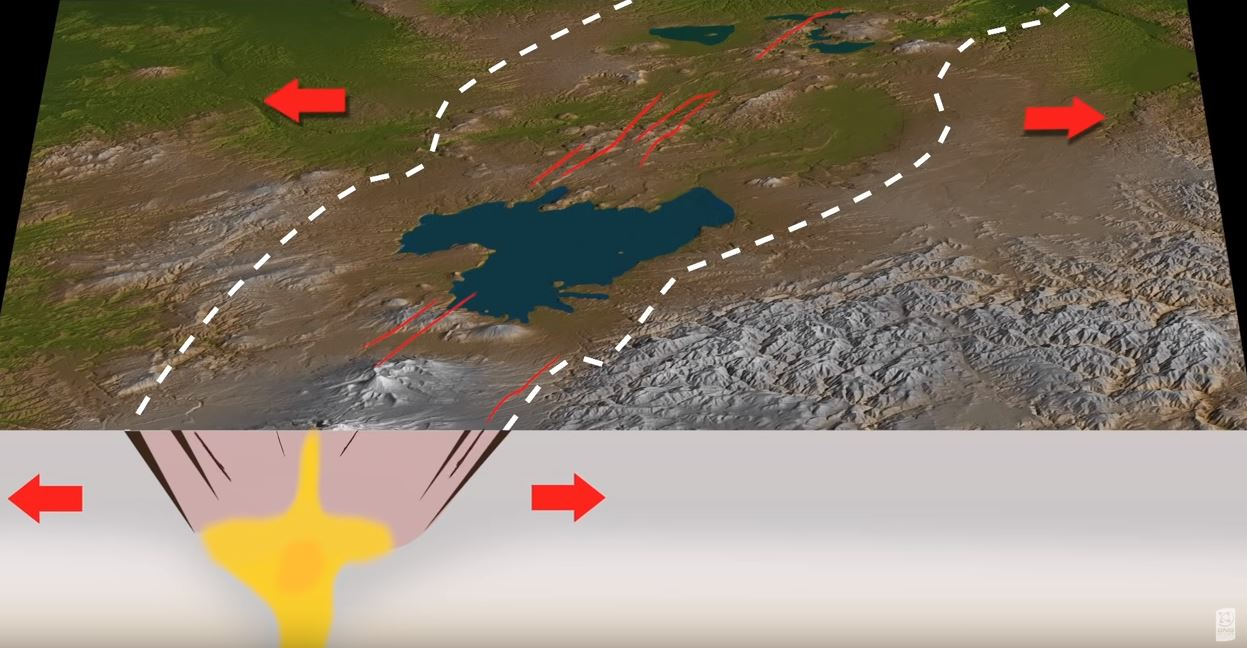

The greater Rotorua-Taupo area is a busy area as it’s a rift zone, where a wedge of the earth’s crust is being stretched due to plate boundary processes. This stretching creates numerous faults which cause many earthquakes over time, including many smaller quakes clustered together as swarms.

Over on the East Coast there was a slow-slip event during March to June, during this time we recorded many small-to-moderate earthquakes in the area, including a M5.1 on 14 May. The total movement along the Hikurangi Subduction Zone during this slow-slip event is estimated to be about 20-30 cm, which is equivalent to roughly four-to-five years of plate motion there. Looking at it another way, if this had ruptured in a single ‘typical earthquake’ it would likely have been similar to a M7.0 earthquake.

The largest North island earthquake was a M5.9 earthquake in November, and in the South, Milford Sound had a M5.5 earthquake in August, both events were felt widely throughout their respective Islands. But the most felt event went to a M4.0 earthquake in Porirua that received 14,577 felt reports! As a comparison the M7.8 Kaikoura earthquake had 15,840 felt reports.

Landslides

In January a cliff collapse event occurred at Cape Kidnappers, injuring two people. Our landslide team was deployed to the area to gather data for research as well as for input into future work, ensuring that appropriate information is available to maximise public safety. These missions are also used to collect reliable landslide data that helps us understand the frequency and magnitude of these events and how vulnerable people are to them.

In March a storm in the West coast resulted in around 350 new landslides occurring and a further 750 pre-existing landslides showed further activity.

A landslide at the beginning of June dammed the small Kaiwhata River in the Wairarapa. Our team were able to take drone footage and GPS measurements of the dam, and work with local council staff to help inform council risk assessments. The dam failed later that month, and we calculated that around 440 Olympic-size swimming pools worth of water and debris flowed over the dam site, over a period of about two hours.

Volcanoes

During 2019 only two of New Zealand’s active volcanoes were showing any volcanic unrest. That is Mt Ruapehu and Whakaari/White Island.

The minor volcanic unrest behaviour that has characterised Mt Ruapehu throughout the past 16 years continued during 2019. During the early part of 2019 the Crater Lake (Te Wai ā-moe ) was in a heating phase, with the lake temperatures reaching 44C in April, along with moderate levels of volcanic tremor. The lake then cooled to 14C in mid-July, before rising to around 23-25C where it remained for the rest of the year.

Whakaari / White Island has been in a state of elevated volcanic unrest since 2011, with explosive and extrusive eruptions in August 2012, Feb-April, August, October 2013 and April 2016. This state of unrest continued into 2019. In the early part of the year the crater lake level was receding, and the volcano was relatively quiet. Around mid-year the volcanic gas output and lake level started to rise. In the active vent area small-scale jetting and steam explosions of mud and debris started to occur in August. The level of volcanic tremor also started to rise slowly.

By November the level of volcanic tremor had increased at the volcano and we increased the Volcanic Alert Level to Level 2 (moderate-heightened volcanic unrest). At the beginning of December, the moderate-heightened volcanic unrest continued with explosive gas and steam-driven mud jetting from the active vent area at the back of the crater lake as well as continued elevated volcanic gas emission and seismic activity. Unfortunately, an eruption with tragic consequences occurred on December 9 at 2:11pm.

Tsunami

Our single tsunami of the year was from a M7.0 Kermadec earthquake in June, which generated a small tsunami at Raoul Island, measuring around 0.1m at our two tsunami gauges on the island. The earthquake was 955km north-east of Whakatane and felt by 190 people in the North Island of New Zealand.

NGMC

And finally, our National Geohazards Monitoring Centre (NGMC) turned one in December, as the team was busy with the volcanic response we delayed their birthday, and plan to celebrate (and have cake) next month! The team also celebrated this month with the centre clocking up 25,000 earthquakes since opening in December 2018. (This number includes all earthquakes detected including New Zealand, Kermadecs and further far afield.)

Although we can’t prevent natural hazards, we can prepare for them – and we should.

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) have a great website with information on what to do before, during and after each type of natural hazard. There you can also find Tsunami evacuation zone maps for around New Zealand And what supplies you need in an emergency.

The Earthquake Commission (EQC) have a helpful website with information on how to get your home, apartment, or rental prepared for a natural disaster.

If you use an Alexa device there is even a Natural Hazards Alexa Skill, an official collaboration between EQC, GeoNet and the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA). Check it out on the Amazon Skills Website.

And if you are going to check out the volcanoes in the Tongariro National Park this year, The Department of Conservation (DOC) have lots of information on the hazards in the park and how you can be prepared.